Institute on Religion in an Age of Science (IRAS) email list

12

12

|

|

|

|

In reply to this post by Alex

On Naturalism and Science

1. Naturalism is the belief/tenet/conviction that every entity and episode, whether directly or indirectly recognized or as yet unrecognized, in the realm of sensorily perceived reality is in the arena of space and time, and that any entity or episode beyond these are products of human imagination, fantasy, or delusion that human brains are capable of. 2. Science is a systematic and collective effort, anchored to the tenet of naturalism, to understand and explain every recognized element and occurrence in perceived reality in a consistent and rational manner, with the aid of carefully designed instruments, experiments, concepts, and mathematics (where possible). Those who haven’t participated in this trans-cultural human enterprise seldom get to appreciate and value its power, beauty, and magnificence as much as those who do. 3. The tenet of naturalism may be and has been analyzed and critiqued by philosophers, metaphysicians, and other keen thinkers with great acumen and expert logic. In particular their charge that this approach hasn’t been able to account for the extraordinarily unique and wondrous phenomenon of human consciousness is quite justified as of now. The probing scientists would respond that there have always been unsolved problems in science which reflects the complexity of the perceived world rather than the inadequacy of science. 4. My own view is that non-scientific and anti-scientific philosophers/thinkers should exert their talents and trans-scientific methodology to solve the problem of consciousness, and scientists too should continue their efforts too. Hopefully one group or the other will crack the code some day. Nothing is gained by periodically repeating that science hasn’t unlocked the puzzle of consciousness: This is a bit of information that most scientists are quite aware of, and trying to resolve. 5. As of now, a more effective framework (other than a science based on naturalism) has not been developed in human history that has unraveled new aspects of perceived reality as much as the science of the past four centuries. Nor has any other methodology offered more cogent explanations for any known phenomenon. 6. This does not prove that the framework of naturalism and science is correct beyond a reasonable doubt. But the history of the acquisition of human knowledge about the world of perceived reality suggests that as of now there is no alternative mode of understanding and explaining what we observe, much less of acquiring new knowledge about the world. 7. It must be recognized that trans-scientific views, visions, and concepts are no less important for the fullness of the human experience. They often play an even more satisfying, meaningful and essential role in the cultural and emotional dimensions of being human, though they have been relatively awkward or sterile in attempts to understand and explain the world coherently. Varadaraja Raman September 8, 2012 |

|

|

This post was updated on .

In reply to this post by Alex

In summary, I've argued that the actual "main divide" is between two fundamentally incompatible epistemologies, one grounded in skeptical empiricism and one that employs methods like faith, intuition, revelation, and divination as ways of knowing. It's good that many religious leaders respect science and want to be in harmony with it, but as long as their members employ faith-based epistemologies and insist on supernatural explanations for certain physical phenomena, then that harmony will be compromised. Yes, we can always improve science education, but major gains in acceptance of scientific knowledge require challenging competing epistemologies and claims. Genuine compatibility between science and religion is a noble goal and can only be accomplished in one way: reducing dependence on faith as a way of knowing and replacing supernatural beliefs with scientific knowledge (as has happened since the beginning of science, see: heliocentric model). In short, this goal will require a major shift in the role of religion away from being a competitor with science regarding truth claims and towards applying reliable knowledge to the art of living.

Regards, Ash 17 Feb 2013 To: irasnet@biology.wustl.edu |

|

|

In reply to this post by Alex

The scientific art of Odra Noel

http://odranoel.eu |

|

|

This post was updated on .

In reply to this post by Alex

Perspectives on Naturalism

http://www.iras.org/perspectives.html A brief Introductory note by V.V. Raman The ancient Greek word for Nature was physis, which gave rise to the word physics. However, to Aristotle and others, nature did not connote what the word means to us (plants, trees, rivers, lakes, stars, etc.), but rather whatever has emerged and grown in the world. The term naturalism has a variety of connotations in various contexts. In the 19th century art, it generally meant concordance with Nature such as Nature seems to be, in contrast to imaginative and romantic elements in the created work. It is related to, but not the same as, realism and Verismus. In French literature, naturalism referred to the style which described in meticulous detail every scene and gesture and character, furnishing the description with an authenticity that was very much like the precise observational data of scientists (naturalists), recording especially the ugly, seamy and unpleasant realities of life rather than idealistic visions and soothing fantasies. The works of writers like Gustave Flaubert and Émile Zola illustrate this framework most effectively. In this literary context the Greek word for naturalism became physiocracy, referring derogatorily to works like Zola’s Nana and Flaubert’s Madame Bovary in which morally taboo and erotic material is explicitly presented to the reader. In the context of philosophy, Naturalism is closely tied to the natural sciences which are based on the tenet that everything that can be known is ultimately connected to one facet or other of Nature. What this implies is that there is a natural cause for everything that we observe, that there are processes in nature (detected or as yet undetected) that give rise to phenomena in the world, that nothing happens at random at the whim of unseen principles, that all observed phenomena can be explained in terms of the laws of nature, and without invoking transcendental principles. Appealing to the scientific worldview, Naturalism is closely tied to what is known as pure materialism. Some critics have contended that Naturalism offers no ethical framework, nor any room for aesthetics, and much less a spiritual dimension to life. They hold that its primary merit lies in its fruitful successes in the domain of the sciences, but that it does not rest on unshakable philosophical grounding. Needless to say, there have been a great many debates and controversies on the usefulness of pure Naturalism as an all-embracing philosophy. Poets and philosophers have reflected differently on nature, especially in relation to God. To William Cowper, “Nature is but a name for an effect whose cause is God.” But Robert Browning flatly said, “What I call God, fools call Nature.” Shakespeare wrote like a poet-scientist, “In nature’s infinite book of secrecy a little I can read.” In the following anthology, ten thinkers from the IRAS family present their perspectives on Naturalism, some on its relationship to Religious Naturalism, which is an important dimension of IRAS. I would like to thank all of them for graciously responding to my invitation to write for this anthology. Comments on their views may be posted in the IRASNET or IRASRN listserves.  Philip Hefner: Naturalism - Full-bodied and God-intoxicated Tom Clark: Varieties of Naturalism: Some Reflections Tanya Avakian: Naturalism as I View It J.Ash Bowie: My Perspective on Naturalism Gene Troxell: My Perspective on Naturalism Michael Cavanaugh: What is Naturalism? Rosemarie Maran: My Perspective on Naturalism Ed Lowry: My Perspective on Naturalism Jerald Robertson: My Perspective on Naturalism Stan Klein: My Perspective on Naturalism Katherine Peil: My View of Naturalism |

|

|

This post was updated on .

In reply to this post by Alex

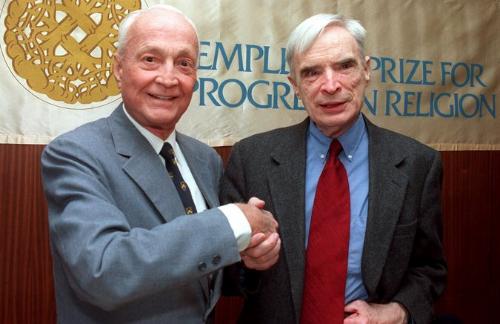

Ian Barbour, Who Found a Balance Between Faith and Science, Dies at 90

Jan 12, 2014 The New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/13/us/ian-barbour-academic-who-resisted-conflicts-of-faith-and-science-dies-at-90.html  Ian Barbour, right, who had physics and divinity degrees, with Sir John Templeton after winning the Templeton Prize in 1999. Marty Lederhandler/Associated Press In 1999...he won the Templeton Prize, a prestigious award given annually to "a living person who has made exceptional contributions to affirming life’s spiritual dimension"..."If we take the Bible seriously but not literally," he said in his acceptance address, “we can accept the central biblical message without accepting the prescientific cosmology in which it was expressed, such as the three-layer universe with heaven above and hell below, or the seven days of the creation story." He was well known for describing four prevailing views of the relationship between science and religion: that they fundamentally conflict, that they are separate domains, that the complexity of science affirms divine guidance and finally — the approach he preferred — that science and religion should be viewed as being engaged in a constructive dialogue with each other. |

|

|

In reply to this post by Alex

On chance and outcomes

There are several levels of physical reality. At the mesocosmic level of planets and stars, as well as motions and transformations at our everyday level, the inexorable laws of nature lead to a determinism that is orderly, calculable, and predictable. At the level of molecular motion, the calculable and predictable aspects are restrained to the statistical level because of the very large numbers involved. Then there is the microcosmic quantum level where strictly deterministic laws give way to a fuzzy indeterminacy that is still within the bounds probabilistic computations. But the built-in indeterminacy is profound: We can say how many uranium nuclei from a sample will decay in the next hour or week, but we cannot say, even in principle, which of the nuclei in the sample will do that. [The famous psi-function comes in here.] Next is the level of Chaotic indeterminism where again there is no telling precisely which path the hurricane will take. Then there is the surreptitious role of chance in the formation of planetary systems: why so much mass was concentrated in a particular planet and why it happened to be formed at a particular distance from the central star? These are questions that cannot be answered by any calculation. These are chance factors that determine initial conditions. Then there are chance factors that affect on-going processes. Factors causing species-differentiation and the evolution of living organisms are governed largely by chance factors which are largely unpredictable. Finally there is the hypercomplex level at which thoughts are generated in human brains. There is no way one can predict how the next thought will emerge from a brain – how, for example, Rosemarie will send her next post or how Michael will react to it. This is because there is no embedded causal factor at the hypercomplex level. Indeed, hypercomplexity is a necessary condition for creativity (the emergence of something altogether new), both in ideas and in events. It is at the root of art and poetry as well as of the twists and turns of history. V. V. Raman Jan 31, 2014 |

|

|

In reply to this post by Alex

On feline fuzziness in QM and CTE

It is worth recalling that Schrödinger brought in what has come to be known as his cat in order to show the absurd consequences of the Copenhagen interpretation. It was in this context that he introduced the word Verschränkung (entanglement) which has come to play an important role today. More than four decades ago Paul Foreman and I wrote a paper on "Why it was Schrödinger who developed De Broglie’s ideas." [Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences 1 (1969)]. I recall reading in that context some of S’s correspondence with Einstein who warned that it was dangerous to tinker with the notion of physical reality. I once expressed the view that the Schrödinger’s Cat paradox arises from what I call Context-Transference Error (CTE). Truths valid in certain contexts, if transferred to a different context will create confusion, lack of understanding, and paradoxes. If we apply classical electromagnetism to the hydrogen atom, the electron will zoom into the nucleus. You need a different set of laws (Bohr’s conditions). Likewise, if you apply the wave aspect of matter and Born’s probabilistic interpretation of the psi-function to macrocosmic entities, you will get the Schrödinger’s cat or dog paradox. [There can be no Schrödinger’s horse, because the animal is too big to be put into a box :-)] The CTE principle should be obvious in certain everyday contexts: If you apply the rules of soccer while playing basket ball, there is likely to be confusion. If you try to build a Ganesha temple or a synagogue in Saudi Arabia, there is likely to be an explosion. And yet, people keep committing the CTE all the time which is one reason for many ideological and conceptual conflicts in the world. This is not to say that we must not have debates and arguments, but to recognize that some of these arise because the opponents are holding positions which are valid in quite different contexts. V. V. Raman February 2, 2014 |

|

|

In reply to this post by Alex

From: Emily and Gene

Sent: March 05, 2014 To: irasnet@googlegroups.com Subject: [IRASnet] science and scripture I have not been participating in this discussion. Ash has been presenting my views on the matter. However, I decided to go ahead and put my views into my words. I may have a more offensive way of presenting this view than Ash does. But I will try not to offend. I see science and traditional religion as very different, not comparable in any way that makes sense to me. Science arrives at its material through examination of the actual world we inhabit. It has its own specialized processes for examining different features of our cosmos. For conclusions worthy of acceptance the scientists arriving at the conclusions must demonstrate that the evidence they consider to support their conclusions are in accord with scientific methods of arriving at such conclusions. Religion, on the other hand, to the extent that it presents an image of our actual world or of history that is in conflict with scientific conclusions, bases its conclusions only upon writings, written thousands of years ago at a time in which very few people could read and write. The writers had world views and intellects that were extremely primitive by modern standards. In most cases they were not even writing about events they claim to have personally witnessed, but events that they claim other people witnessed and then reported. In many cases the event supposedly occurred at least a hundred years before it was reported in written language. Once structured religions developed by people taking these writings seriously, the leaders of the religions were considered qualified to make further statements concerning features of the idea of the world based upon these writings. In some cases the statements of these religious leaders were considered "infallible." They could not make an error in describing further aspects of the nature of the world formed on the basis of the writings, even though evidence was never even considered relevant to the conclusions they reached. (I suspect some of the conclusions stated by leaders of early Christianity may soon fail even in the minds of the modern adherents of the religions in spite of the fact that at the time they were stated they were considered to be infallible.) This is enough for now. What has not been covered is the relationship between science and traditional religions concerning the meaning or purpose of human life and matters of ethics. Most of you know I already have plenty to say about those matters, but I will try to summarize my views in another post. Also I want to emphasize that I am talking only about matters in which religion and science present conflicting ideas about history or the nature of the material world. I am not considering the wisdom concerning how to live that is present in some religious writings. Best Regards to all Irasians, Gene |

|

|

In reply to this post by Alex

IRAS Summer Conference

Date: 23-30 June 2018 Place: Star Island http://www.facebook.com/events/1999611763661856 “I’m sorry Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that….” said HAL in the most famous line in 2001: A Space Odyssey. So Dave had to disable HAL to regain control of the spaceship and dodge annihilation. From the earliest myths of artificially created beings until today, the question of “who’s in control” has troubled us. Now it looks like we’re really going to have to deal with it in our lifetimes. On the 50th anniversary of 2001, IRAS returns to considering the prospects, opportunities and dangers of Artificial Intelligence (AI), first discussed at an IRAS summer conference in 1968 by Marvin Minsky, a founder of AI research and consultant to Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke as they directed and created 2001. This conference will address how AI may shape our future as well as our ability to foresee and control how AI will reshape us. Deep learning neural networks and advances in big data manipulation have led to rapid progress in machine learning and associated capabilities. Investment in AI will grow more than 30 times between 2016 and 2020, to at least a $50 billion industry. New AI products will enhance sales, data analysis, and diagnostic and predictive services for medicine, government, science and industry. We are on the cusp of creating machines that can operate in environments that require significant autonomy, such as self-driving vehicles and, ominously, weapon systems. The future of AI is likely to have powerful consequences related to jobs, income distribution, criminal and social justice and our polity in general. This growing international commercial and governmental juggernaut, itself subject to concentrated and frequently unaccountable control, presents just one of AI’s many challenges. How will humans identify and find meaning in life as the breadth of skills unique to living, sentient beings shrinks? The consequences of the interplay of AI and the human mind, and our very self-concepts, are likely to be equally profound. If we succeed in creating science fiction’s “conscious” machine, what would be our duties to it (as well as its duties to us)? The values and orientations fostered by a religion and science perspective will be crucial to the responsible development and utilization of AI technology as it unfolds. We will review the current state and potential future developments of AI technologies and consider the following questions as seen by AI experts and those in related fields: * What are the true benefits of AI for the future of society? * How do we assure ourselves that all of society will truly benefit from AI? * How can we avoid the various pitfalls that are now being debated concerning the control of AI in the future? * What are the ethical, social, legal, and religious factors that ought to be considered to assure the benefits of AI for society? * What is the appropriate role of religious wisdom and traditions in helping to maintain this control when considered in more secular ethical, social, and legal circumstances? * How can religious wisdom and traditions, in particular, inform more secular deliberations about controlling the future of AI? * What are the roles of religion and science in contributing to the dialogue to optimize the benefits of AI to society? * How can we create an ongoing process to maintain human control of the future of AI? Program Co-chairs: Terry Deacon and Sol Katz Conference Co-chairs: Abby Fuller and Ted Laurenson |

«

Return to Philosophy, Theology, Religion 哲學、神學、宗教

|

1 view|%1 views

| Free forum by Nabble | Edit this page |